Meet the mite, the tiny bugs in your mattress, your tea and on your face

From the tea we drink, to the water we swim in, to the beds we sleep upon, millions of minuscule mites share our wide world. Mites are arachnids, much like spiders and scorpions, and the microscopic creatures are among the oldest and most plentiful invertebrates on the planet.

“There are at least between 3 and 5 million species of mites, and that is a very conservative number,” said mite expert and U.S. Department of Agriculture Entomologist Ron Ochoa. “Almost every beetle will have a mite. Almost every single plant has one to three mites. The soil has mites. The ocean has mites. Humans have mites. Any mammal has mites.”

Ochoa works for the USDA’s Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit in Beltsville, Maryland, an agricultural research facility that allows scientists from around the world to get high-resolution images of the mites they are studying. The facility also plays host to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History’s mite collection that contains more than a million different mite specimens representing more than 10 thousand species. NewsHour paid a visit to the facility to see what’s under everyone’s skin.

Ticks — the blood-sucking, Lyme disease-carrying subclass cousin of mites — are considered the largest of the kind, but most mites are much smaller. The tiniest mite on record is 82 microns long. That’s barely one third the width of a human hair.

The Spinosaurus mite is named after the Spinosaurus dinosaur because of its enlarged back fin. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit

Ochoa credits the mites’ unseen dimensions for their ongoing success. “In the beginning that they didn’t really need a large size, and they are still around because they are escaping our ability to see them,” he said. “Humans are completely oblivious. Walking all around, feeling like they are the center of the planet while they are surrounded by mites.”

Gary Bauchan works closely with Ochoa as director of the microscopy unit. Armed with an arsenal of various microscopes, he and his colleagues take intimate looks at mites, fungi, bacteria and other microscope minions. So far, the team’s images have landed on the covers of more than 30 scientific journals.

Some of their most detailed photographs come from the lab’s low-temperature scanning electron microscope, a technology that literally captures a moment frozen in time.

“Most of the time in an electron microscope, you have to put mites in a fixative and kill them, and then they tend to shrivel a little,” said Bauchan. “Now, the other way is to freeze them in liquid nitrogen. So whatever they were doing at the time we froze them, that’s what they are doing in the microscope.”

Some mites are helpful, benign creatures. Others, not so much. Check out just a few of the mites Ochoa and Bauchan have studied below.

Rose lovers beware. The rose rosette disease mite (Phyllocoptes fructiphilus) is a good mite gone bad. In the 1970s, this mite and a virus it carries were used as a biocontrol agent to kill wild roses in farming areas.The virus causes a rose bush to produce too many buds, which the plant can’t support. At the same time, the mites feed on the host’s juices, and the rose plant eventually dies.

Scanning electron microscope image of the “Rose Rosette Disease Mite”. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville, MD.

The rose rosette disease mite didn’t stop with wild roses — now, it threatens the wider ornamental rose population. Because the mite hides from predators in the hairs at the base of the flower buds and leaves, options for stopping infections are few. “The irony is the hairs are there to protect from insects but because the mite fits under them, it protects itself from predators that can kill him,” Ochoa said. “The mites not only seeks out the plant but uses the plant’s defenses to protect itself too.”

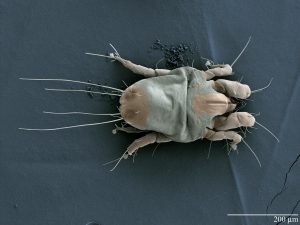

The house dust mite (Demartophagoides farina) is one of three known species of dust mites in the world. The non-parasitic mites feed on dead skin cells. They take up residence in humid, room temperature habitats like mattresses, pillows, carpets and other household surfaces with easy access to the human body.

Scanning electron microscope image of the “House Dust Mite”. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville, MD.

In America alone, more than 20 million people suffer from dust mite allergies. But they aren’t reacting to the mites themselves. “If you say you are allergic to dust mites, you aren’t allergic to dust mites. You are allergic to the stuff that’s left after a dust mite feeds on your skin,” said Bauchan. “It’s mite poo that you are allergic to.”

Speaking of mites that feed on human material, Demodex folliculorum (Simon) is one of three mite species living on your face. The microscopic critters are found across the human body, but are particularly dense near the nose, eyebrows and eyelashes. They live in the body’s hair follicles feeding on the gland’s secreted oils. At night, an army of mites — researchers estimate more than 1.5 million on average — come out to mate and consume built up gunk around the hairs.

Scanning electron microscope image of the “Simon Mite”. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville, MD.

But these mites aren’t considered harmful. “You have them, but your immune system doesn’t identify it,” said Ochoa. “It’s like your immune system associates them with being part of your body.”

Ochoa is fascinated by the fact that these facial mite are transferred from parents to children through close, prolonged contact. Researchers analyzing the mites’ DNA can actually trace a person’s geographic family origins over the course of generations. Still, scientists estimate 0.01% of people don’t have any Demodex mites.

“For me, that is the big question,” said Ocoha. “There are several hypothesis. Number one is that they were born by Caesarean, and number two is the mother didn’t breast feed the kid.”

Scanning electron microscope image of the “Peacock Tea Plant Mite”. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville, MD.

Odds are you’ll think about the “Peacock” Tea plant mite (Tuckerella japonica) the next time you sip on the hot beverage. Originally from Japan, T. japonica is now found across the world and uses a whip-like tail for defense and dispersal. The mites feed on stems and fruits of tea plants and may affect how the tea tastes.

But whether the mites are actually in your brew remains to be seen. “We don’t know for sure if the mites make it into the tea you drink, especially due to the processing that the leaves go through prior to packaging the tea,” said Bauchan. “However, the tea and its mites have had a long association, and there is still a lot to learn.”

And finally, the Red-legged earth mite (Penthaleus dorsalis) is the new kid on the block. It was first described in 1911 on winter crops grown on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. This was the last time that the mite was seen until 2012, when Ochoa and Bauchan got a call from organic farmers in eastern Maryland.

Scanning electron microscope image of the “Red-Legged Earth Mite”. Photo by Gary Bauchan, Ron Ochoa and Chris Pooley/USDA – ARS, Electron & Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville, MD.

“We went out to see the problem, and their pea plants were black with the mites,” said Bauchan.

Even identifying the species proved difficult since red-legged earth mites are cold resistant and simply walk off the frozen plate used to examine them.

“The mite was walking on the -20 degree Celsius [-4 degrees Fahrenheit] plate like its us walking on a beach,” he said.

Since 2012, the species has also been found on collard greens, bok choy and broccoli crops in Delaware, Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejmLamusKeZqadlal6rrXLpaCopqNiuqqzx62wZqWZqbK0ecuirZ5loKGur8DSZqernaSpxm651JyfZp2mmr%2B6w8eeqZ5llaHApg%3D%3D