The dirty, painful death of President James A. Garfield

Editor’s note: This post contains graphic content and may be disturbing to some readers.

On Sep. 19, 1881, James Abram Garfield, the 20th president of the United States, died. His final weeks were an agonizing march towards oblivion that began on July 2, while preparing to leave Washington for a family vacation to the New Jersey seashore.

A man of great energy, eloquence and charm, Garfield was in a superlative mood that morning. At the breakfast table, he horsed around with his two teenaged sons while singing a few patter songs written by the musical kings of his day, Gilbert and Sullivan.

READ MORE: Marilyn Monroe and the prescription drugs that killed her

A few hours later, the president was strolling through the Baltimore and Potomac train station. Before he reached the platform, a mentally disturbed lawyer and writer named Charles Guiteau broke through the crowd and entered the history books. He shot Garfield twice. The first bullet grazed his arm but the second passed the first lumbar vertebra of his spine and lodged in his abdomen. Fully conscious, in awful pain, and unable to stand, President Garfield cried out, “My God, what is this?”

A battery of Washington doctors rushed to the scene. One of them, an expert in gunshot wounds named Doctor (no joke, that was his first name!) Willard Bliss, ultimately became Garfield’s chief physician.

Fully conscious, in awful pain, and unable to stand, President Garfield cried out, “My God, what is this?”Focused on finding and removing the bullet, Bliss and the other doctors stuck their unwashed fingers in the wound and probed around, all for naught and without applying the numbing power of ether anesthetic. In late 19th century America, such a grimy search was a common medical practice for treating gunshot wounds. A key principle behind the probing was to remove the bullet, because it was thought that leaving buckshot in a person’s body led to problems ranging from “morbid poisoning” to nerve and organ damage. Indeed, this was the same method the doctors pursued in 1865 after John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln in the head.

President Garfield was taken back to the White House where the medical treatment truly became brutal. Still hellbent on finding and removing the bullet, the doctors argued whether it damaged the spinal cord (Garfield complained of numbness in his legs and feet) or one of the many organs in the abdomen. Dr. Bliss even recruited Alexander Graham Bell to apply his newly invented medical detector to find the errant bullet.

As the summer waned, Garfield was suffering from a scorching fever, relentless chills, and increasing confusion. The doctors tortured the president with more digital probing and many surgical attempts to widen the three-inch deep wound into a 20-inch-long incision, beginning at his ribs and extending to his groin. It soon became a super-infected, pus-ridden, gash of human flesh.

This assault and its aftercare probably led to an overwhelming infection known as sepsis, from the Greek verb, “to rot.” It is a total body inflammatory response to an overwhelming infection that almost always ends badly — the organs of the body simply quit working. The doctors’ dirty hands and fingers are often blamed as the vehicle that imported the infection into the body. But given that Garfield was a surgical and gunshot-wound patient in the germ-ridden, dirty Gilded Age, a period when many doctors still laughed at germ theory, there might have been many other sources of infection as well.

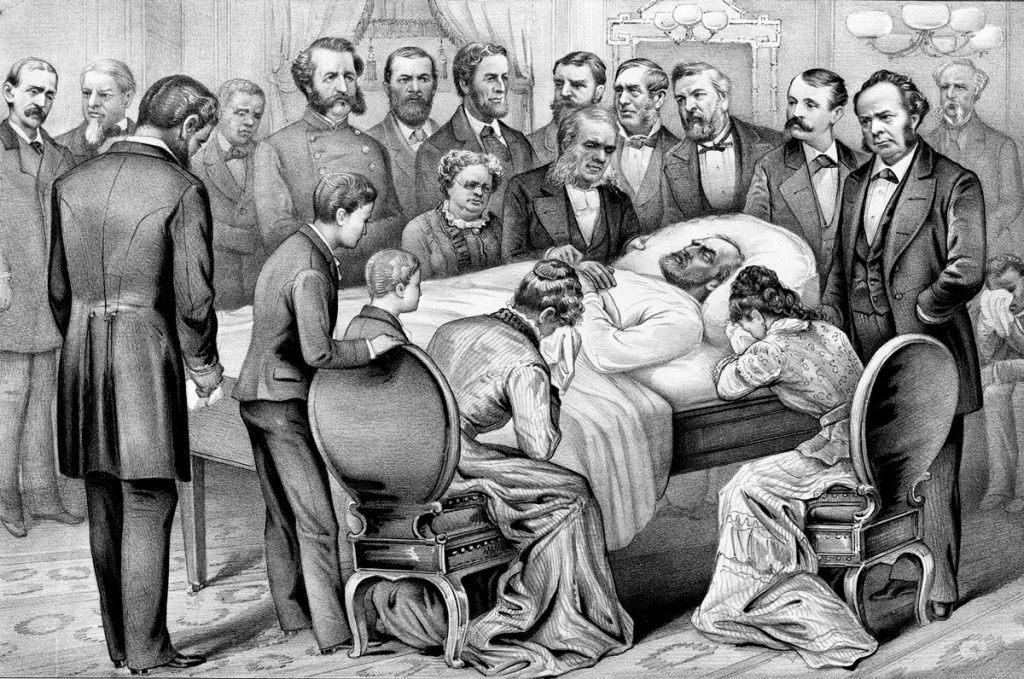

During his last 80 days of life, Garfield wasted away from a plump 210 pounds to a bony 130 pounds. On September 6, a special train transported him to his seashore cottage at Long Branch, New Jersey. The president’s final breaths were inspired on the evening of September 19. Clutching his chest and wailing, “This pain, this pain,” he died. Without the aid of a stethoscope, Dr. Doctor W. Bliss raised his head from the president’s chest at 10:35 pm and announced to Mrs. Garfield and the medical retinue, “It is over.” The assigned causes of death include a fatal heart attack, the rupture of the splenic artery, which resulted in a massive hemorrhage, and, more broadly, septic blood poisoning.

There is, indeed, a grain of truth to the assassin Guiteau’s claim “the doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him.” But this odd and disgusting medical history requires a more nuanced clarification.Guiteau was later found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, even though he was one of first high-profile cases in American history to plead not guilty by reason of insanity. He was hanged on June 20, 1882, in Washington D.C.

In recent years, a wave of revisionist historians has taken Garfield’s doctors to task for not applying sterile technique, and, thus, saving the President’s life.

There is, indeed, a grain of truth to the assassin Guiteau’s claim “the doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him.” But this odd and disgusting medical history requires a more nuanced clarification.

To be sure, in 1881, when Garfield was shot, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch were at work scientifically demonstrating the germ theory of disease to great public acclaim. Beginning in the late 1860s, the surgeon Joseph Lister beseeched his colleagues to apply these discoveries and adopt “anti-sepsis” in their operating rooms. This technique required surgeons and nurses to thoroughly wash their hands and instruments in anti-septic chemicals, such as carbolic acid or phenol, before touching the patient.

The number of surgeons who actually followed Lister’s edicts of cleanliness as late as 1881, however, was few and far between. From the distance of more than a century, it is tempting to imagine that germ theorists, or “contagionists,” overtook “anti-contagionist” medical practices with the speed of light. In real time, however, many mainstream physicians and surgeons did not fully adopt anti-septic techniques until into the mid-to-late 1890s, and for some, as late as the early 1900s.

Blaming his doctors may be a tantalizing literary trope but President Garfield had an excellent chance of dying from the ordeal no matter who treated him during his awful, last summer. The annals of medical history are littered with such retrospective diagnoses that can never really be proven but, nevertheless, make for great medical tales. Nevertheless, Bliss and his colleagues certainly cannot be credited with helping Mr. Garfield all that much.

In the final, post-mortem analysis, the president desperately needed a modern medical miracle long before his doctors were equipped to produce one.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eYmq6twMdom6KqpK56sa3Ip52upF2ZsqLAx2anq52jnrGmutNmoZqllah6qK3Rn6CepJQ%3D